Tagged: society

4 Magical Political Words

Because they can mean anything to anyone.

1. Affordability

This word is often used in the context of public service delivery, such as with housing, public transport, healthcare, and education. Then there is also things to do with costs of living as in, “Singapore is becoming less affordable”. Of course, the sharp-witted public will immediately point out that affordability depends on the who’s using the service, and who’s producing the service. And oftentimes, the range of people using a public service can be very wide, and so the term should be used for the lower-income deciles, where affordability of public services can be a make-or-break difference in how they can save enough for their family or to make a living. So instead of simply asking whether public services are ‘affordable’, people should be asking, “how much is the increment of service x, and how are the lower-income people shielded from the effects?” For the rest of us, the question of affordability should really be – is my income rising faster than the increments? If yes, ignore news, if no, then… well…

2. Sustainability

This term is so often used that its becoming an empty phrase. In popular use, sustainability is used in the environmental context (as I remembered it being used in the early 90s) – as a term to look at the longer-term viability of the natural environment and to preserve it for succeeding generations. In my recent memory, the term is being used to describe the financial viability of public finances and with economic growth, as with “sustainable economic growth” – as with China – which is confusing because it can describe both the environmental aspects and the viability of 7.5% and above GDP growth.

So I propose that sustainability should really just be replaced with “longer-term soundness (or viability)” – which is what most people are trying to get at. However, this only solves half of the problem; the other half is that people don’t seem to understand that longer-term viability depends on the flows of production, consumption and (re)cycling mechanisms – that’s why I guess it was used first in the environmental context, and now looking at financial contexts.

When I think of public schemes, I think of cash transfer and other such subsidies. In self-reliant Singapore, one question that pops is whether such transfers and subsidies are “sustainable or not?” That’s really quite simplistic, because such transfers or subsidies really assume a wider context of economic growth or some other stable condition. Without that linkage to income flows, questions of longer-term viability are just not worth addressing.

“But maybe increased transfers can make public finances less sound?” Well, *shrugs – that really is a political question, on how much people want to receive, and how much we believe that taking care of each other is important. As for soundness well, unless country X hired Y financial company to fiddle around public finances, I wouldn’t be too worried. I hope common sense prevails, of course, that people fundamentally understand that soundness basically just means spending within means and save something for the future. Because there won’t be an external party to bail us out.

3. Engagement

This really is a representative of the various terms used to describe government-society relations. How much input should the public and civil society groups have in considering policies? What are the political considerations for the political parties taking part in these kinds of exercises? In SIngapore the second question of political parties is often ignored, but this might not always be the case. My attention is on the first question – and that has been addressed in one of the articles in Ethos magazine on the spectrum of engagement, ranging from inform, to consultation, to consensus-building, and then co-creation. In summary – there are many forms of communications, some of which cannot be told to the public, some of which requires feedback especially on technical affairs, others are more open and wide-ranging, when some others require the public to act first. All of these depends obviously on the context of the situation, and the outcomes to be achieved. Slapping “engagement” on every single government-society interaction dilutes the term of its meaning, and increases the cynicism and confusion when such events takes place.

4. Inclusiveness

First of all, if some spokesperson say that country X strives for inclusive growth, does that mean that country’s economic growth was exclusive to some people? Martin Luther King Jr’s civil rights movement was about political participation as it was about economic participation for ethnic minorities. The platform on which he gave his historic, “I have a dream” speech was the “March on Washington for Freedom and Jobs”. Most people would seem to have an intuitive sense of what inclusive growth means – that broad segments of the population can participate and enjoy the income growth that comes with a growing economy. But as the financial crisis revealed, growth can focus on very narrow sections of the working population, with some sectors enjoying nearly astronomical increases in their income. That in turn, can be attributed to political-structural issues; on the impact of the finance industry on politics; on the diminishing influence of labour and the continual pro-business and anti-welfare slant – all of which as happened in the US, and some of those have some resonance with what has happened elsewhere in the world.

The other facet of inclusiveness that’s also not often talked about but intuited at is the notion of socio-economic mobility and more egalitarian distribution of incomes. The other side of inclusive growth means upward economic mobility. Is that possible? Let’s think in terms of what happens when someone works in a large company. In the company, upward economic mobility depends on the size of the company, how many units and divisions and departments are there, and the complexity of the businesses it engages in. In a large company, there are many units and subunits, so there are more rungs in the ladder to climb. But as one goes higher, the rungs get fewer and fewer, and ultimately only one person can become the CEO or the president or managing director. So upward income mobility has limits. However, if the company becomes bigger through acquisition or expansion, then more people can join in and climb their own ladders. And so it is with the economy. The economy is composed of many companies and industries in interaction with each other and the world. If there isn’t much change in the size of the economy, then the number of rungs in the corporate ladders don’t change so much. It means that the opportunities for income mobility won’t change much as well – there will be limits in how high one can climb in the ladder. Of course there’s yearly increments, and I’m simplifying things. [Would definitely appreciate comments from economists/smarter people here. I’m prepared to change my mind on a lot of the things here.]

And that’s just in the economic sense. Inclusiveness also has other connotations, to do with people with disabilities, handling religious and ethnic diversities, and inter-generational differences. Singapore wasn’t always a kind place for people with disabilities and for older people and even today, it can be a far kinder place. There just seems to be gaps in the society’s culture that prevents us from experiencing and empathising with people who might actually have real difficulties in getting around and living a better life. It is always emotionally easier to deal with something far-off and in a stand-offish way in abstract terms, than to begin to try to understand the difficulties of those people and the people who love them. Recent efforts by Caritas in asking people to walk with the less privileged is definitely notable, but a lot of it also depends a lot on employers and managers to understand their needs and work alongside them. The question of social inclusiveness will also re-connect back to economic inclusiveness – by asking people to get along with others different from themselves, they too can get access to economic opportunities and live meaningful lives.

Another facet I want to get to about inclusiveness is that it also leaves many other questions about what gets left out, and if new social groups are included in some new scheme, why were they left out before? These questions are also, ultimately, political in nature – about political figures being accountable to the public on the delivery and intent of some of these policies, especially where strong attitudes/inclinations/stigmas/prejudices still exist. Again the topic of inclusiveness is about how expansive and embracing do people want to be.

Lastly, inclusiveness is also a question of identity and how secure people are with the identities thus constructed by politics and by culture. Who are we? Who do we choose to be? In my mind, and this may be arbitrary, but these questions are mainly cultural, and sculpted by political and social groups in contestations.

So here they are: 4 magical political words: which when used achieve the political objective of broadcasting favourable imageries into people’s minds and especially so, when not questioned.

And, Merry Christmas, and a happy 2014!

Happy 48th, Singapore! Many Happy Returns!

On National Day I cannot say that I unreservedly love the country. In my mind, I can easily provide counter-responses to the reasons why Singapore is worth loving. The to-and-fro as I imagine, would sound like this:

“Singapore is my home, where all my family and friends are!”

Retort: “If you are able, you can easily move your family to an Asian neighbourhood in a different country, and make new friends. You mean you cannot make new friends in other countries?”

“Singapore has low crime!”

Retort: “Just find a safe neighbourhood, or live in a gated community.”

“Singapore is multicultural!”

Retort: “You haven’t been to NY, London ah?”

… And on and on.

Ultimately, the basis for our patriotism is emotional. There’s just this emotional connection that we feel, and when we celebrate National Day, we celebrate this emotional connection. No country is perfect, and Singapore is no more or less imperfect than other country. By sheer choice of deciding where we want to belong, individual and national identities co-mingle, and it’s on that basis individual Singaporeans come together and decide to celebrate National Day.

—

I don’t want to overstate how good or bad Singapore is, but to state some of the facts: material growth contrasts with growing inequality; education anxiety is as high as ever with more tuition centres; I don’t know if the the structural unemployment is more or less of a problem; our transportation system is expanding – the “step” improvements in capacity contrasts against the creeping increase in population.

And here I speculate: I wonder if the physical constraints lend themselves to a zero-sum sense of the world. I would think so, and as I read Edward Glaeser’s Triumph of the City, I come to terms with how the impulses for environmental and historical preservation can be opposed to the need for development, and to keep housing affordable. Supposing if, one day the pretty shophouses at Katong have to make way for more high-rises for an increasing population to keep housing costs affordable – what then? Despite the genius of Singapore’s urban planners, there still is only so much that can be done, and very difficult choices have to be made. Today one of the choices is already before us: that the Cross-Regional Line will be cutting through the Bukit Timah Nature Reserve, and the Nature Society has already provided a report and alternatives about the routes that the line could take. If the land transport agrees to the alternatives, it can be seen as having compromised to environmental interests. Yet in another way, Singaporeans and future passengers of the CRL would also have won – to be able to both enjoy nature, and to enjoy cheap and quick transits across the island. In a physical sense, some of the choices are indeed zero-sum.

—

In policy and national issues, the central frame can appear to be zero-summed – that the gains of someone must mean the loss of another. The rat-races in education and materialism (5Cs) also demonstrate the zero-sumness frame – that the achievements of someone means someone else’s loss, or even my loss. Rankings tend to have this framing – everyone has ‘their place’, and one can only progress at the expense of another. If Singapore should thrive in an uncertain future, then we’ll all have to progress together.

People live in families, in communities, and in societies. No one truly lives alone, and no one is truly independent of another, or totally self-reliant. Being reliant on others isn’t so much a personal fault as it is a necessity: how can we live relying only on ourselves?

My own thoughts are that Singapore’s future progress will come from what Singaporeans will give to each other, particularly those who have been marginalised, and neglected. Some of them might not even be Singaporeans, and we’ll still give all the same.

This spirit of giving, of accepting compromise and to do so in amicable ways, could define the way the big G deals with people, communities and organisations and shape the future to come.

—

Here’s to many happy returns. Happy 48th.

Edit: There won’t be a post over the weekend! Happy Long Weekend, Singapore!

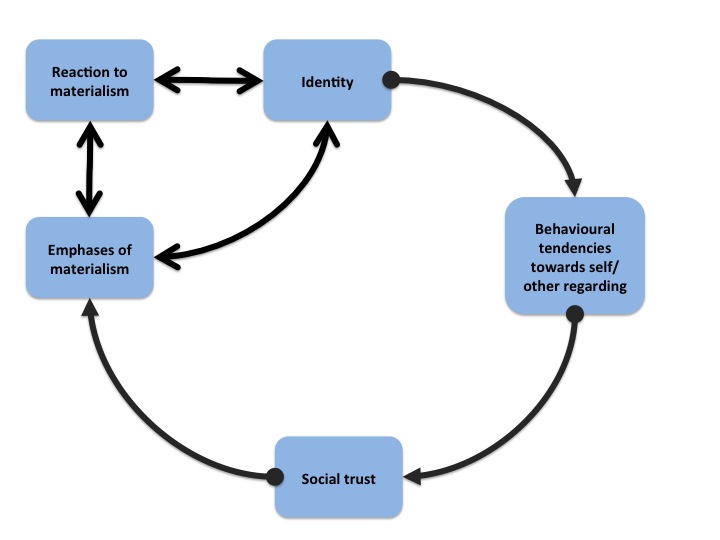

Identity, and Materialism

I’ve been wondering about the relationships between materialism, personal security and self identity, and the cultural attitudes in society. How firmly do people believe that material possessions are an important source of identity? Where do we get the sense of attachment from? And how does that relate to how we interact with other people? Do we believe more in closed zero-sum interactions (as being Kiasu could imply), or in more open, non-zero sum interactions?

Singaporeans are surrounded by material abundance, but to as phrased by Laurence Lien, we could be in a “social recession”. How is this possible? I don’t know. How is that the material abundance we have is not clearly evidenced in the abundance of compassion and spirit?

Identities

This week is about individual identity.

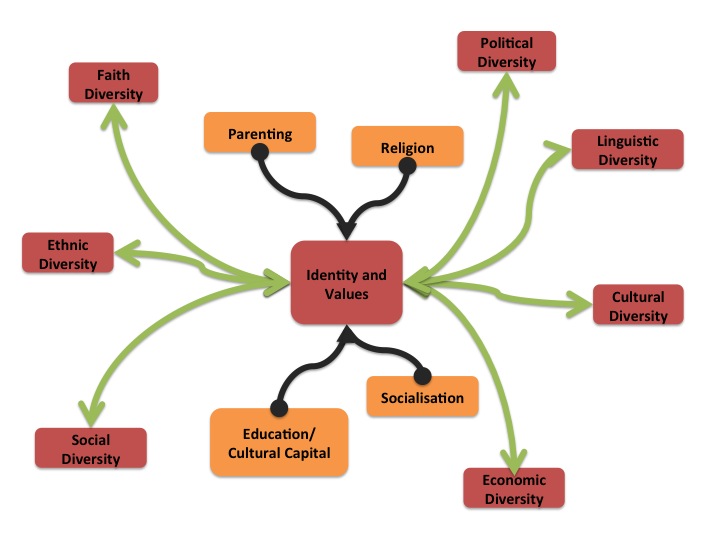

Where do we get our identities from? Parenting, faith, religion, education and socialisation all have something to do with it, and the identities and values they nurture help the individual interact with the diversity of society around us. Are we equipped to do so?

I volunteer at Explorations Into Faith, a group of people that aims to engage with the diversity of faiths (and non-faiths) in Singapore. You can find out more at their website here: http://eif.com.sg/

Also, a talk by Andrew Solomon, author of Far From the Tree, talking about horizontal and vertical identities, and the love that conquers all. An extensive book review by Maria Popova here: http://www.brainpickings.org/index.php/2013/06/12/andrew-solomon-far-from-the-tree/

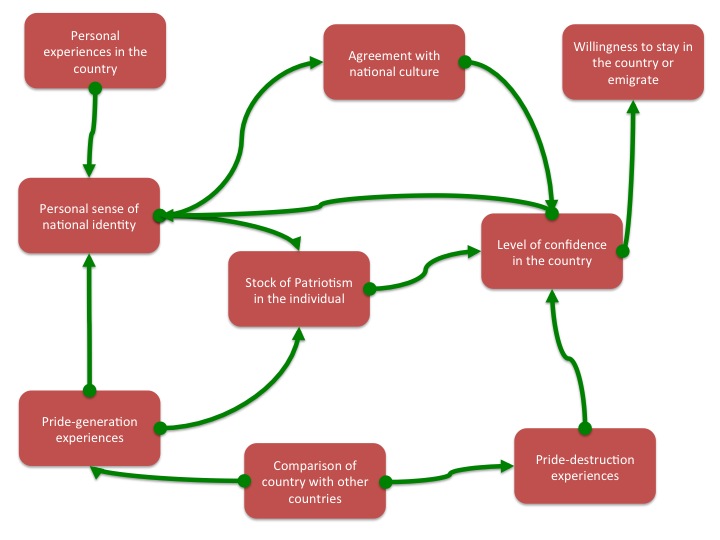

Patriotism

The map of the week is about patriotism.

This is a purely-sentimental driven map, although things like economic opportunities could be interpreted in terms of the pride and identification that one has with the country, as with “I appreciate the opportunities I have in this country to realise my abilities”. In a similar way, ownership of property can also be interpreted in the same vein, as with, “I appreciate the fact that I can own my own home.” And then there are pride-destruction experiences, such as losing confidence with the political leaders, losing employment, seeing discrimination perpetuated by authorities of one form or another. This isn’t specific to any country, and I guess the weights of countries will be different. In others, the identification with a local or a national culture (if one exists at all) could be more important than pride for the local region or community.

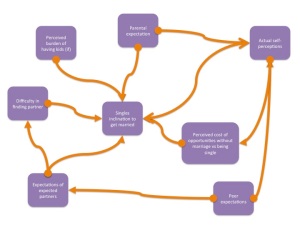

Marriage and Choices

This week, it’s something micro. This is a hypothetical relational map about what goes in when couples are deciding whether or not to get together.

We take for granted that lifelong-monogamous relationship with one partner has been the not-so norm among human institutions. I say, “not-so” norm because it’s an ideal thats routinely broken – no one can point specifically to an age where lifelong monogamous relationships happened without occasions of adultery (by either gender).

The lifelong-monogamy I imagine made sense economically, with divisions of labour splitting along gender lines. Individualism, gender equality movements have made marriage less compelling (for either gender, and more so for females). The reaction so far in developed societies is to let-it-be; accept serial monogamy (people divorcing and remarrying), slowly sorting out child-custody issues (allow dads some rights in raising the kids), lowering the barriers to single-parenthood…

I realise that many of these things are legal developments too. Should laws conform to the attitudes and conventions of the current age, or should they reflect some notion of rights? The former could be used to justify racial segregation in the US; the latter might be too unrealistic for acceptance by ALL sectors in society. What then, what next?

The last point is methodological: I admit that a lot of the variables or qualities or concepts usually assume the rational person, in making decisions using some notion of cost/benefit analysis, and reduce the weight of other factors. What I’ve tried to do usually, is to factor in social expectations as well – and this is one way to incorporate the non-rational, or non-economic rational. I still think this encompasses the way we make choices, that we do consider a lot of the variables together, but the framing of these variables matter. I think what a systems-based representation does is to clarify at which point of decision-making does the framing matter. They could come at the initial process of scanning; at the middle part as they get processed; or at the end as they consider preliminary impact of the choices guided by the framing. Of course they could also happen at every/any stage of the process too. There’s no good way, and it’s up to the individual analyst to choose where does framing matter the most, or if it’s in the background of things.

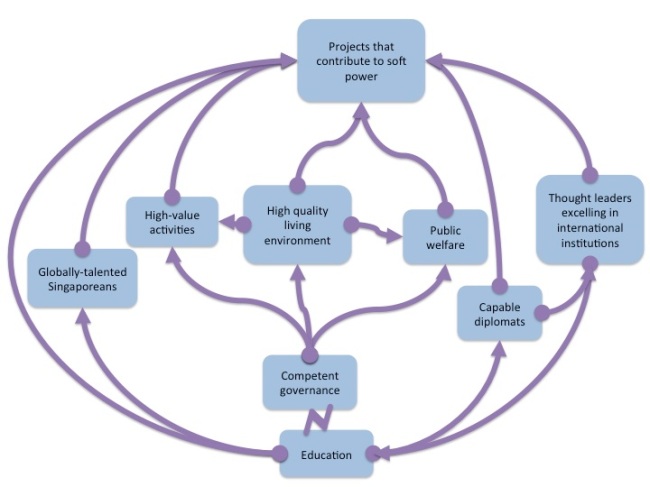

Soft Power

I’ll be away over the weekend, so I’ll posting this early.

I look at soft power, and try to break it down into its constituents. This is at best, a guess of what soft power might comprise.

In this short analysis, soft power just means running a country well and getting admiration from other people. As long as the basics can continue, Singapore will continue to be a “net exporter” of soft power.

Change is Incredibly Hard to Accomplish

To implement change is possibly the hardest thing that anyone ever has to do, if they choose to do it. Moreover, change itself is a dangerous thing – be careful for what you wish for; you might very well just get it.

Ok, enough of the cryptic, truistic sentences. What did I really mean? Change is difficult to implement – that’s a truism – everyone accepts the inertia of existing systems, the power of existing incentive structures, and the risk that comes along with the changes in incentives. The fact that there are frequent changes in the bureaucracy is itself a minor miracle – proving that there are internal entrepreneurs who are willing to take risks and implement changes. This description is by itself, too simplistic.

The changemaker has to mobilize people to his/her own side – get others to believe strongly, that a change is required, and to follow him/her into believing in the change, and to accept the consequences that come with the changes. The changemaker has to engage existing stakeholders in the system, and convince them that the new system to be birthed, with their own set of indicators, will not cause them to lose their previous positions, and that they can benefit in the new paradigms. Winning everyone over – that is clearly not a task for the fainthearted. Along the way, the changemaker will encounter cynicism and criticism – people who may have tried something similar before, failed and sidelined; there are others who might have something to lose in the new situation. At every stage towards change, the changemaker has to find ways to neutralize these criticisms, either by bringing them on board, or circumvent them, or summon additional resources (having someone superior in position to the critics helps).

What does mobilisation mean? That means meeting people, and empowering them with the permission to influence others, as the original changemaker does. The original changemaker has to be ok with the idea that their followers are going to be, if not more, popular than he originally is. As time progresses, the relationship between the original changemaker and others will change along too. The changemaker has to have a persevering personality – to have the emotional stamina to withstand the many meetings and responses that would be expected in a change exercise. The exhaustion is to be expected; the changemaker has to find ways to recharge and continue with the journey.

Movements splinter when some of the followers realize that they can do the same things without acknowledgement or subordination to the original changemaker. “Hey, the [changemaker] is not as great as I thought he was at the beginning. I can do this on my own if I wanted to.” In a bureaucratic setting of risk-aversion, the likelihood of such changes happening might be smaller, if only because people are ‘used’ to the idea of following orders from someone else. The hierarchical nature of bureaucracy lends itself to less division as power is neatly territorialised – everyone individual has a demarcated sphere of influence; to breach into the spheres of others require permission from different parties. That is why change in a bureaucratic setting is also harder – especially if the change cuts across different ‘territories’.

Change also has unintended consequences – hence the, “be careful for what you wish for – you might just get it.” For example, in a autocratic, illiterate society, control is easy – have a few simple messages that people can understand, and everyone could live with. Improving education access, and people can learn about the misery of their situation and demand democratisation of their country. The example is certainly simplistic, if only to demonstrate that introducing the idea of change, and in empowering people to act for themselves, can result in outcomes not anticipated. Introducing empowerment in a hierarchical system could result in internal dissension and dysfunction as a whole, preventing vital functions from being performed.

The content of change is not a trivial thing, nor is it something that can be done as a sideline. In a bureaucracy, performing change is an extra burden on top of the main work that has to be done. In society, performing change is such a major activity that people start up organisations – civil society, political parties or even companies to achieve their vision of change. I don’t believe that there are many people who have the conviction to see through their own visions of change (including myself). I admire and applaud others who have done the same, and wish them well.

Parenting and Cultural Frames

The parent-child link is one of the most powerful and mysterious bonds that I think we are hardly able to understand. This is also undoubtedly a private/intimate matter, but unless there is a serious conversation about the values we choose to let our children imbibe and to facilitate the environment for consistent transmission of these values, we cannot proceed productively as a country. We will still be talking past each other, fail to empathise with the positions of each other and the difference in the journeys we take in life.

In a sense, Our Singapore Conversation is a process for us to hear each other’s journeys in life and to appreciate the vast differences in life experiences. This is not about judging between these different journeys, but to appreciate them for their own sake.

There is another implication to understand the parent-child transmission of values. Recognising that parents are an obviously important means that a lot more attention ought to be paid to how parenting is done, the character of the parents themselves, and their state of mind as they bring up the kids. There is a small aside about the importance of parenting – prospective drivers need to be tested before they are allowed on the road; surely something as important as parenting ought to be greater attention to by the society? If we demand our kids to go to schools taught by qualified teachers, surely, when they go home, they ought to be cared for by parents with the requisite skills? And what could those requisite skills be? (I do realise that there’s a programme called Marriage Preparation Course, but I don’t know if it’s an official or informal programme; whether its mandatory for couples and such.)

There are two main modes of cultural transmission – the child receiving cultural frames from the parents, and what the child finds for themselves in the outside world. Parenting provides the framing for the kids to learn from what they see in the outside world. Of course the kid will learn things on their own anyway. Then the question is, where does the parent get their worldviews from? And is the environment conducive for the healthy kind of parenting that we idealise about?

The social scientist in me says that parenting is obviously part of a larger system that includes values, and the social groups and arrangements, and the economic system. Sheryl Sandberg and Ann-Marie Slaughter discuss the role of women in the working world, and the kinds of challenges they face being woman – still taking on the assumed role of primary caretaker to the children while reaching the pinnacles in their professional career. What about us? Sandberg and Slaughter represent the pinnacles; what about the majority – including those who struggle to between work and home a whole lot more? For some parents, the interactive screen has sort of become the surrogate parent – I say ‘sort of’ because its a toy thats given to the child to pacify the demands for interaction, which the busy parent cannot afford as much struggling to at work in a hyper-competitive environment. I’m reminded of the “Illustrated Primer” in Stephenson’s Diamond Age – where a young girl escapes dysfunctional parents, and comes across an interactive book, with digital avatars becoming surrogate parents. That’s a digression, and obviously an extreme case. We are nowhere near the point where interactive digital environments can replace flesh and blood parenting – but the point remains that parenting is one of those things for which the rhetoric does not match up to real attention.

How would greater attention on parenting look like? I know that religious bodies do a bit of that, and some of them have the resources to integrate prospective parents into religious schools for kids – for them to know what parenting entails and to know how little kids are like. And new parents will always find a way – forums, grapevines, and other channels that must have existed wherever anxious parents exist. Should Marriage Preparatory Courses be made compulsory (if it isn’t already)? One of the things that’s come about with an individual culture is that adulthood is assumed to “just happen to you” when you start to become financially independent and paying for your own bills. Yet obviously adulthood is almost so much more than that – such as learning to live with the consequence of your choices, that your own choices will both liberate and constrain, and all the other invisible obligations that we don’t know about until we crash into them.

I have explored a bunch of attitudes and ‘myths’ that abound in society, and I have only touched on the historical context a little bit. I want to go a bit more into them – such as trying to imagine the life experiences of those more advanced in years. When we talk about differences between generations, what I often missing is the empathy to imagine what others might have gone through in their lives. I will be trying to do a lot more of that soon.

A Primer, A Hypothesis: In SG, stuff gets done

I had the opportunity to join in an in-depth discussion of Singapore issues at the National University of University. Was nice to be back in University Town to be back with USP friends. The discussions was rushed but still robust. And during the discussion, a particular thought came up, that “in Singapore, things get done“.

In a presentation later, the notion dawned upon me that for various reasons, GSD isn’t just a productivity geek culture getting things done in a distraction-rich world. GSD – Getting Stuff/Sh*t Done – has been ingrained in us for a while now – 2 generations and counting. We have demonstrated over the decades, that we have been able to get initiatives going, get mega-projects done, pull through from crisis, and doing a really good job of accomplishing the goals we set for ourselves. In Singapore, things get done, and we aren’t too shabby at it.

I used the “we” in a collective sense – for the people who have made visions realized – from the politicians through to the construction workers who have built the projects. Yet I also know clearly that this national obsession with GSD also has all kinds of unintended side effects. I’m wondering if our obsession for ‘deliverables’ has got anything to do with it. In previous occasions, I used to think that it was clearly for accountability, in the ‘what do you have to show for it’, but I’m also beginning to wonder now that part of this has to do with the expectation that whatever we do will have an applicability component to it – “it will be useful, and this is how it will be useful”. Even in the OSC, the demands that something ‘tangible’ to show for the process was initially attributed to just general impatience, but after this framing, it’s also because Singaporeans also like things to get done. Clearly for somethings, the process is genuinely useful as a way to get in touch with other Singaporeans, and to see their point of view. The discussion content merely comes out of that sharing of perspectives.

There are also more serious side effects, such as how we might have ignored all kinds of sensitivities – in the enthusiasm and rush to get things done, emotions are brushed aside as ‘subjective’, policies can become inaccessible and cumbersome to navigate, and people have to put up with all kinds of temporary inconveniences for some abstract greater good. Perhaps the clampdown on political expression in previous times was also an expression of GSD as quickly as possible, without having to do with political contests.

There are other things that GSD has no comment on. I’m not sure what the appropriate rationalisation is for GSD to comment on the things of skewed income distribution, the tuition-obsession, the refusal for a more substantial social welfare system. GSD is only one part of a larger system of values that we embody, and there are several others.

Maybe this is also the reason why there’s always a bit of doubt about the purpose of subjects such as history, literature or philosophy, wherever they are thought. It’s not just because these subjects are difficult to ‘score’ in, but that they are about things that are not objective oriented – they are not about getting things done – in that sense. These subjects are about explorations for their own sake, in learning about the crafting of words as with literature, or learning about how our narratives are created, as with history. And maybe ‘worst’ of all – philosophy – thinking about thinking. In this sense, Alfian Sa’at’s repsonse to this national aversion to literature in sceondary/high school is brilliant, and to quote it in full”

“A question I was asked: What more can be done to arrest the trend of dropping Lit candidature? Do you think it is an inevitable trend?

My answer: Yes, I think it is an inevitable trend. And I don’t think it’s necessary to arrest it at all. Look at the speeches in parliament, or even the columns and editorials in our mainstream papers. There’s hardly anything literary about them, and yet they get their points across. I think we should stop measuring ourselves against other countries that have deeper cultures and traditions and accept the fact that we are this mercantile, pragmatic, tough-minded city-state that has no time nor inclination for the effete humanities. I think it’s perfectly fine if our main cultural diet consists of Channel 8, Jack Neo movies, anthologies of ghost stories and self-help books. As a people we are kiasu and crass and ungracious. But why should there be shame in any of that? We’re already a First World country, and cultural capital had no role in determining this particular achievement. One of the indices of ‘first world’ human development is literacy, not literature. This anxiety to acquire ‘high culture’ is actually part of an aspirational third world mentality, and we should feel secure with our own brand of smug philistinism.”

Another issue with “GSD” as an ethos is simply that GSD has no stand over the content of the stuff that gets done. And GSD also doesn’t fully explain this national impatience about needing things to be done quickly.

I guess the GSD ethos only assumes that small fixes get done – after all, for various reasons, Singaporeans only care about what gets done in the here and now – fixing the MRT delays; reducing property prices; meanwhile the longer-term horizon becomes hostage to short-term exigencies. What then, what next, what else?